When Self-Perpetuation Overtakes Mission

0 comment

Every data point confirms that the nonprofit sector keeps growing and all indications are that the growth is not slowing down. GivingUSA told us this week that for the second year in a row, giving in both real and adjusted for inflation dropped in 2018. Another source tells us that the percentage dip in giving increases as the amount given decreases. In other words, smaller donors are disappearing faster than those who give bigger gifts, defined as $1000 or more.

Coupled with my concerns about a double digit growth is that increasingly, nonprofits seem to be forgetting who they are and why they exist. They seem to have forgotten that as a 501(c)(3) they exist because they convinced the IRS that they are, indeed, working on behalf of some portion of the public good.

Yet the behavior I too often see suggests they are working for organization and job preservation, not on behalf of their client population.

One of the easiest places to witness this behavior is in those nonprofits that refuse to shut down. Each month poses the question of whether they will make payroll. They live hand to mouth, with no cash reserves, no bankable assets, no safety net, no Plan B.

When attention is diverted month after month to trying to keep the organization afloat, attention is not going to being the best for and best by clients. Instead, we are looking at self-perpetuation. When donor after donor expresses no interest in funding their work, the handwriting is on the wall. Either they don’t believe in what you do, don’t believe in how you do it, don’t believe in the people you have doing it. To keep on carrying on isn’t about doing well by clients but about perpetuation of someone’s vision, even if others aren’t sharing that vision. There are clear signs along the path that mandate our attention—declining income, fewer clients, increased competition, difficulty in getting staff and board members—and demand a proactive response, as opposed to what too often happens: burying heads in the sand.

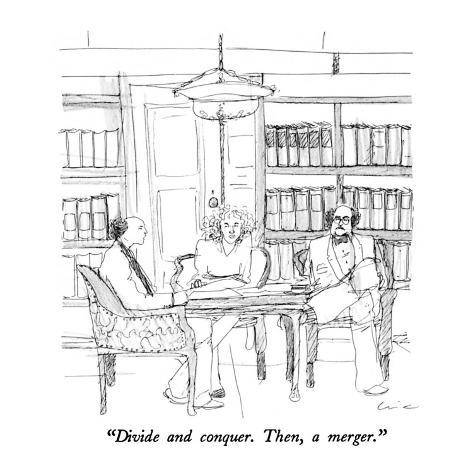

Another testament of this behavior is how too many mergers happen. Mergers should be the result of a very intentional, strategic process with the end goal of making two organizations more effective than either was on its own. Mergers should not be the result of convenience or laziness. Yet, again, I see this too often.

When a board seizes upon the pending departure (voluntary or forced) of the executive director as an opportunity to merge because: a) they don’t want to go through a search and/or b) the organization has been struggling for several years they have allowed comfort and ease to trump serving others. If a board has determined that a merger is needed to ensure that the organization can continue to serve best its clients, that merger should not be dependent upon when the executive director is leaving.

Yes, a big stumbling block in nonprofit mergers, and one that often derails them, is which executive director will lead the merged organization. When one is out of the running for whatever reason, that merger just became a lot easier and lot less fraught in the eyes of the two boards. No feelings have to be hurt, no one will lose a job. It becomes a merger of convenience rather than a strategic merger. Such a merger is generally not the result of the necessary discovery process, seeking out and assessing alternative merger partners in order to find the best one to maximize the new organization’s ability to meet client needs, crafting a strategy for organization integration, etc. It is all done for the board’s (and executive director’s) benefit.

Boards taking mergers as the alternative to doing the tougher work of assessing the organization to determine if it should continue, hiring a new executive director, and more, is not out of synch with a growing desire on the part of boards to do less rather than more.

I am stunned and saddened by the growing frequency with which I’m asked if it is okay for boards to meet quarterly. I am concerned by the increasing incidence of complaints I get from executive directors and good board presidents about board members failing to attend meetings, inability to make quorum, unprepared board members, and more. None of these complaints is new; it is the frequency with which they are coming that is. Boards don’t want the responsibility of really overseeing a nonprofit, of doing their job, but they want the “cache”, and accompanying kudos, of being able to say they serve on a nonprofit board. It isn’t about making sure clients are served; it is all about them.

Another indicator of boards and staff more concerned with themselves than the welfare of clients is the number of programs that operate without collecting and using impact data. Yes, designing program evaluation requires work; yes, collecting impact data requires work; yes, there is no point in collecting impact data if it isn’t used to understand what’s working and what’s not and make adjustments. Beyond being additional work at multiple levels, evaluating program impact is scary. Why? Because staff see it as threatening their jobs, board members see it as threatening their favorite programs. It isn’t about doing the best by clients, it is about protecting jobs and pet projects.

But the one thing that most readily convinces me that we have lost focus on why we exist is organizations’ refusal to ask—and answer—a very simple, but oh-so-important question: do we still need to exist? As the environment in which we all work ebbs and flows, issues come and go, nonprofits come (mostly) and go, the need for every organization also ebbs and flows. The need for an organization is not static, despite what so many would like to think. If we keep front and center that we are here to serve others, not ourselves, then how can we help but ask whether we are still needed, still necessary, still the one?

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.