Second-Class Citizen

0 comment

We recently got a request from a smart executive director who wanted to enroll in our Certificate in Nonprofit Management. She thought it would be a good thing for her, as she could learn new things, get a refresher on old things and expand her network. But, she didn’t know how to justify this to the Board. Her request: did we have any data that showed the benefit of pursuing this professional development opportunity?

What? Isn’t what she enumerated justification enough? If need be, however, there is plenty of research out there that demonstrates the value of providing professional development opportunities for employees: it correlates with greater job satisfaction, improved job performance, improved morale, and more. But what really got me going is that I know that this woman’s board is predominantly made up of people from the for-profit world, the world where professional development is as expected and accepted a practice as saying “hello” each morning to your colleagues. So, why would they be resistant to such a suggestion?

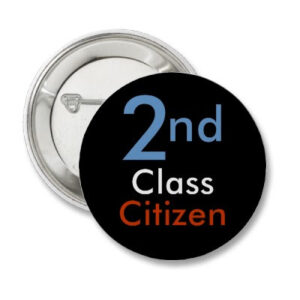

And then I started thinking of all of the practices routinely accepted—no, more than accepted, actually expected—and seen as beneficial in the for-profit world that fail to thrive in the nonprofit sector. And I have NO answer to the question “Why”? Except that the nonprofit sector, once again, is seen as a second class citizen and not deserving of all of the rights and privileges of first class citizens!

My examples of expected practices that float easily in the for-profit world and struggle in the nonprofit sector:

- Professional development: as noted above, almost de rigueur in the for profit world, is a luxury in the nonprofit world.

- Interim chief executive officers: how many major, successful for-profit companies have experienced the benefit of an interim CEO? One who comes in and turns things around, rights the ship, whether that ship was on the verge of sinking or merely needed a subtle move to get out of a shaky current? Some organizations do need a major overhaul, while others just need a change in perspective, style or personality, for example. In the for-profit world, an interim CEO is often welcomed as an indication that the board of the organization is doing its job, whether that means it is replacing a CEO no longer right for the times, buying some time to do a good permanent hire, bringing in someone to make needed but painful changes. Yes, it makes some investors weary, and it is one of the things that stock analysts point to as potential investment risk. But there are also times when those very same analysts will say that an interim CEO is positive for the company’s bottom line. I’ve yet to see any advisor or analyst categorically say “No, do not invest in a company being managed by an interim CEO.”

Yet, in the nonprofit sector, far too many funders have policies (and practices that are so entrenched they may as well be policy) that categorically forbid funding an organization led by an interim CEO. Never did understand that policy, as hiring an interim is one of the signs of an organization looking to improve. Members of nonprofit boards of directors whose for-profit companies may be being lead, now or in the past, by an interim balk at the notion of putting in an interim CEO at the nonprofit for fear of “what it will say to our donors.” What? Like we are in charge? We saw a wrong and we righted it? Our executive director left on short notice and we wanted to buy time to hire well? We are losing our founder/long-serving executive director and we need space and time to figure out the new normal before we can hire correctly? How is it that something seen as so good in one sector is seen as a sign of weakness in another?

- Competitive salaries: I almost do not know what to say here as it all seems so obvious! Regardless of what sector of the economy in which those employed work, all are working to make the communities in which we live and work better. We need banks and law firms and gas stations just as much as we need social service, education, health care, and arts organizations. While employees don’t all want the same kinds of jobs, all want to be able to have a quality life style. Why, oh why, oh why do we think those working in the for-profit sector deserve access to a better quality of life than those working in the nonprofit sector? Why is competitive compensation such an expected part of the for-profit world and seen as anathema and an affront to the nonprofit sector?

- Executive and senior level coaching: This spring, my son, in his last semester of college, started looking for a job post graduation. He had a conversation with his uncle, CEO of a Fortune 500 company, and asked him, among other things, how to differentiate offers from similar types of companies. My brother’s immediate response was look for a mentor; best advice he gave him. One of my big laments about the nonprofit sector is that we do a lousy job at mentoring, and an even lousier job at providing coaching. Mentoring is free, and yet we still see it as an intrusion on our time to serve our mission. Coaching admittedly costs, but it is an investment in the future of the organization and the sector. For-profits get this ROI and are willing to spend both time and money for the return it inevitably brings. Why don’t we?

- Strategic planning: No one likes doing it, but at least the for-profit world doesn’t spend as much time trying to avoid doing it as doing it. Those in the for-profit sector understand the value and importance of it, the benefit it brings to the organization and its employees, the commitment it demonstrates to investors. Strategic planning is taking control of an organization and its future; it is giving it direction, goals and differentiation from the pack; and it is giving the organization and its employees’ confidence. Without that plan, an organization is blowing in the wind, and anyone who has spent time in a wind tunnel knows that is not a position of strength! And yet, too many nonprofits see strategic planning as an imposition and a diversion from mission. With a goal of producing 10% more wickets, that wicket factory is not diverted from its mission, but rather 110% focused on it! With a strategic goal to open 100 more stores over the next three years, that bank is not diverted from its mission but singularly focused on achieving that expansion and doing so in the most cost effective and efficient way. And yet, more often than not, nonprofits come to the planning process kicking and screaming, cursing the funder who made the strategic planning the stick for the funding carrot, complaining that their board members—many of whom have done strategic planning in their corporate lives—don’t want to give up the time for this insignificant work. Really?

What will it take for nonprofits to understand that their singular focus on mission may too often prevent them from seeing the trees for the forest? What will it take for nonprofits to embrace what is good about the for-profit sector, and fight for its installation? And what will it take for board members from the corporate world to stop treating the nonprofit sector with any less care, attention, nurturing—and value—than it does their for-profit world?

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.