Respect. Reward. Resist.

2 comments

More often than not, when people hear the path I have taken from college to graduate school to now, I get a fairly consistent response that suggests that they don’t see how I got to where I am today, that they don’t see my path as particularly linear. But I guess that depends upon how you look at it.

When I look at it, it seems very linear: I have spent my life–not just my career–in different arena within the nonprofit sector, focusing always on gaining knowledge and sharing that knowledge–which is education. Although my current title reads “Executive Director” my profession is educator; I have multi-fold areas of expertise, though I think criminology, always narrowed and focused, is a little out of date, while nonprofits is highly honed and considerably broad.

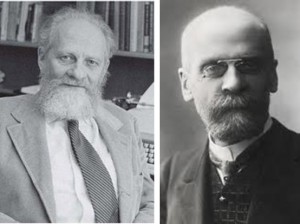

Having read Emile Durkheim, considered by many to be one of the greatest sociologists ever, and Peter Blau, thought by many to be the father of the study of organizations, both in undergraduate and graduate school, their thinking and theories have been in my brain, sometimes in the forefront, sometimes rumbling around in the back. Recently, the ideas of both men have been front and center, as hiring in the nonprofit sector has picked up, and all predictions are that the sector will do even more hiring in 2013. Great news!

But I worry. Too many nonprofits do a very poor job at hiring–be it hiring staff, consultants or other vendors. Why? Simply put, they haven’t read Durkheim and Blau. And because they are cheap, wanting as much as they think they can get for as little as they can possibly spend. So, they end up with generalists instead of experts and a very odd division of labor. A very little Durkheim and Blau could go a long way to making nonprofits be better and smarter organizations and, thus, more successful.

Simply put, with apologies to any sociologists who may be reading this, as I am a great admirer of Durkheim, Durkheim believed that as societies–and organization–evolve, a natural division of labor occurs, as people’s interests and “natural” skills push them to those things that they do best. A society or organization benefits by allowing that division of labor to occur and specialists to develop.

Blau, born a year after Durkheim died, in studying organizations raised the concept of profession, and with his co-author of Formal Organizations, identified, in 1962, six characteristics of a profession. Prior to this, Americans tended to view only three fields as having a profession: medicine, law and clergy. Their six characteristics of a profession, are, in language easy to understand:

- a distinct body of knowledge that only members of that profession possess;

- rigorous training accomplished through education or practical experience;

- automony of practice;

- a professional association;

- a code of ethics; and

- a goal of altruism and not self-service.

In other words, professionals are those who have a “comprehensive and authoritative knowledge of or skill in a particular area,” in quotes because it is the definition of “expert” lifted straight from the on-line Oxford Dictionary, who, more likely than not, have gravitated to that profession because of interest and pre-existing skills, and who come with externally– set standards and colleagues who guide the practice.

So, what is the little bit of Durkheim and Blau that nonprofit employers should know in order to do better in their hiring? Understand that generalists–jacks of all, who cannot possibly be master of any–will not be your strongest assets. Understand that in a complex society division of labor happens because of the growth of specialization and that the skills, knowledge and tools of a trade that are needed to do any one of those specialties is not going to be found equally in all. Concede that professionals have knowledge and experience that you and others in your organization do not and respect it by rewarding it appropriately and stepping aside and allowing the professionals to do their jobs, rather than interceding where not appropriate and resisting when appropriate.

After all, where is the logic in hiring a professional and then letting a nonprofessional interfere with how she executes her profession? And yet I see this all of the time, as executive directors (not a profession by Blau’s thinking) intrude into the work of the development professionals they have hired, or the marketing, program or the financial professionals or consultants they have hired. Where, pray tell, is the logic there? Hire a professional but don’t let her practice? Talk about a loss of ROI! And yet, it happens all the time.

Quite honestly, though, I don’t know which makes less sense: the former, as described above, or this: choosing to hire a nonprofessional because it is cheaper, while hoping that somehow she will do the job that a professional will do. Perhaps over time it will happen; after all, that specific body of knowledge that is the first and foremost trademark of a profession can be gained either through education or on-the-job training, depending upon the profession. So, yes, you could wait it out–and see where you are 12 years or so from now. Again, talk about a loss!

I’m not sure why the nonprofit sector doesn’t value the wisdom that professionals can bring to the sector. Observation tells me it is the age–old Achilles heel of the sector: penny wise, pound foolish.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.

2 thoughts on “Respect. Reward. Resist.”