Take a Board Member to Work Day

0 comment

There are two constant complaints that I have been hearing from nonprofit staff members since my earliest days in the sector. One: Board members don’t understand what staff and the organization do. Two: The board doesn’t do anything, which translates to, staff have no idea what, if anything, the board does. Both complaints are sad commentaries.

I want to be quick to point out that the first complaint is not simply jawing from some disgruntled staff. Decades of experiential evidence repeatedly shows me the staggering number of board members who really have no clue what the organization is all about, what programming it actually does, what the real life situations are of clients, etc.

It is amazing to me how many board members have violated one of my mandates for any board member: no one becomes a board member without having seen the mission in action. That doesn’t mean that every candidate must see every program at work. It simply means that every candidate, before joining the board, must observe at least one program functioning, preferably one that is a core competency of the organization. Seeing all the other programs in action should come with the first six months of a new board member’s service.

Board members are regularly expected to make major decisions that impact clients and staff. Based on what? A mythical understanding of what it is like to be poor or homeless, or addicted, or reading at a third grade level, or living in a world without the arts? Having read about the impact of improper pre-natal care, discrimination and hate, being raised in a homogenous community or a refugee camp?

Recently, I visited an intentionally diverse charter school that is in its first semester of existence. As a member of its founding coalition, I wanted to see the reality. Starting with just kindergarten and first grade classes, the classrooms were packed with kids of every color and many faiths. Almost half are on mandatory free lunch and four families were currently experiencing homelessness.

The staff had visited every one of the 160 families over the summer in order to get to know the families and to gather important information, such as how to contact the guardians and why they chose this school. Curious, I asked about the answers to the latter question. The one that struck me the most was the guardians’ recognition that their children were growing up in a diverse world and learning to navigate that world wouldn’t happen if their children went to their neighborhood school.

How do board members, sitting around a table, removed from staff and client alike, come to understand that there are parents who can’t read, so you can only contact them by phone, or employees who need to take a second job because the salary they are paid makes them a member of the working poor and a consumer at the very food bank where they work? I spent just over an hour, including a sit down conversation with the ED and few hallway conversations with the head of school and a teacher, not to mention stopping and talking to the children as they came into school. I left inspired and informed. What board member of any organization can’t give an hour several times a year?

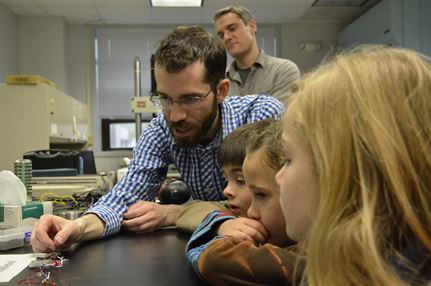

Truthfully, though, were I a board member, that time would not have been nearly enough. So, let’s create a “Take a board member to work day.” Let’s have board members walk in the shoes of staff and see the mission in practice and through the eyes of staff and clients. And, don’t let this be a once and done thing; this is at least an annual occurrence for serving board members. They will not just understand what the organization is all about as a result, and make them better ambassadors and fundraisers, but they will also know the better questions to ask as they sit around the board table.

Board members, however, are not the only ones who don’t understand all of the moving parts. Far too often, the majority of staff—the ones beyond those who work directly with the board—know neither what the board is supposed to do, nor what it actually does. Why is this the case?

First, too often there is a barrier—sometimes in the form of the executive director, sometimes the board—between the board and staff such that the paths of the two never cross (at least in a meaningful way). Each is a mystery to the other.

Second, staff’s understanding of what the board does—or doesn’t do—is the result of hearing the executive director’s complaints about the board’s failures. Too often, that lament is about the board’s failure to raise funds, thereby allowing staff to reach the (oftimes) unfair conclusion that the board is to blame for the lack of resources. As we know, fundraising is a collective and coordinated responsibility, and board members need a lot of nudging and handholding to do their part. Third, because of the board’s failure to communicate with staff, even though things as easy as sharing minutes of board meetings or inviting staff to attend all or a portion of board meetings, boards easily appear to be operating behind the curtain. When people can’t see what the group is doing, but know that it is supposed to be doing something, it is easy to reach the conclusion that the group is doing nothing.

Knowledge doesn’t come without communication; communication can happen in so many and, frequently, easy ways. It is when we fail to communicate that we fail to transmit knowledge that can drive both individual and organizational success.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.