Disruptive Innovation and Puppies

0 comment

Have you ever come across a nonprofit and wondered why something similar doesn’t exist in every community? That was my thought when I read about the Building Goodness Foundation (BGF) in Charlottesville, Virginia. BGF connect “skilled volunteers from the design and construction industries with opportunities to use their professional skills for a good cause.”

In other words, they design, build, renovate and repair facilities for their nonprofit partners.

They’ve provided nonprofits with everything from playscapes to handicapped-accessible outdoor recreational space to community centers and waiting rooms, and more, doing both design and construction together, rather than one or the other, as is the norm.

In choosing projects, they are guided by four goals: (1) to create “high quality buildings” that (2) increase a nonprofit’s ability to deliver on its mission while (3) creating jobs and training for folks in the community and (4) giving volunteers a “transformational” experience while doing good. Like what you see? They will also help others set up BGF affiliates in their communities.

Learning of BGF tied in with the reading I was doing on Clayton Christensen’s work on “disruptive innovation” (DI) and jobs theory. Given that I lead an organization that was founded over 35 years ago to help nonprofits learn from, and adapt best practices of the for-profit sector, I’m increasingly frustrated—and annoyed—by how few of those best-practices there actually are, while the myth that for-profits do it all right and better than nonprofits remains deeply rooted in the hearts and minds of Americans. Thus, I’m always piqued when I learn of interesting things that seem to be working well for for-profits and could have applications in the nonprofit sector.

Clayton Christensen has been at Harvard’s Business School since the 1990s, when he identified disruptive innovation. The name describes the phenomenon, but only to a degree: yes, it is innovation of any kind and it disrupts the status quo—the ways things have always been done, —but it does so with the specific end goal of providing access, includes affordability, to products and services to populations previously lacking such access.

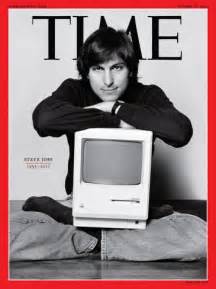

Christensen points to many examples, from Apple’s first computer which allowed millions of people access to what had previously only been available to the few and mighty, to Southern New Hampshire University, which used the principles of disruptive innovation to move from being an unknown institution (not necessarily easily accessible or affordable) to a dominant player in the on-line education space (much more accessible and, sometimes, affordable). DI works hand-in-glove with another of Christensen’s ideas—Jobs Theory. Together they provide a great model for designing new nonprofits (and all nonprofit programming) rather than the historic, normal “model” of: “I have an idea and passion; I want to start a nonprofit/program and I don’t care if anyone else is doing it already.”

Jobs Theory is an alternative approach for understanding market needs and demands. Instead of analyzing consumer data—what male/female of what age of what income bracket buys which product—to determine market need and create new products, Christensen says providers should look at the jobs consumers want and need products to do. This view point makes every purchase of a product/service the result of the consumer looking for a solution to a problem. Understand the problem, and you can design the right product.

One example Christensen has cited is the rise of the retail medical, quick clinics, providing the busy person desiring immediate attention, who won’t sit for hours in a doctor’s office and knows what her/his illness is and wants it addressed immediately with the solution. Identify the job the consumer needs a product/service for and then build the solution.

This duo has been widely used in the for-profit sector, and though Christensen has suggested the approach could be used to solve some of the world’s big social problems, it is an equally intriguing approach for the work of all nonprofits, regardless of the scale of their work. One of the basic rules of DI is that it serves those not currently being served, those for whom alternatives don’t exist. Add to this that disruptive innovation tends to be simpler than current offerings causing a rethinking of expectations, while the products/services themselves improve over time, allowing organizations to do more and more.

Uber, one of the agencies Christensen cites as an example of successful disruptive innovation, has, some would argue, improved its product with time, no longer just shuttling humans to and fro, but also their food and, in a special partnership with local SPCAs, puppies for workplace cuddling and decompressing.

There certainly are examples of Christensen’s concepts in action in the nonprofit sector. The Heifer Foundation was, I would argue, a great example, back when it started, as was Muhammed Yunis and microcredit. And we can point to nonprofit and for-profit DI efforts to bring purified water to those previously without. Christensen’s ideas seem to be work, to some degree, in filling the job at the macro level; but it seems equally missing at the micro level.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.