Absent Retention Strategies

0 comment

I keep hearing from people that the nonprofit sector is at a pivotal point. There is more competition, and not just from within. Threatening the sustainability of the nonprofit sector as we know it: the growth of public-private ventures; the push from millennials to make money while working on behalf of others, spurring the development of pure for-profit companies working to solve society’s problems; the declining number of households supporting charitable enterprises.

I don’t believe that the sector is broken, but rather that we are allowing it to be eroded by our failure to take seriously problems that have long haunted it. Going through the recently-released results of Nonprofit HR’s “2019 Nonprofit Talent Retention Practices Survey” only confirmed this perspective: we are, yet again, our own worst enemies. We identify a problem and then do nothing about it. There was little in what was gleaned from the responses of the participating nonprofits that surprised me. It is time to stop ignoring this data. Here’s a blog post I wrote about the same problem in 2014 and again in 2017.

While I’m not as enamored of this research as I would have been had it been more reflective of the realities of the sector, it nevertheless has value. Whereas the reality is that somewhere between 2/3 and 3/4 of nonprofits have budgets under $1 million, in this sample, just 15.6% of this sample had budgets of that size. Almost 1/4 had budgets between $1 million and $4.9 million, making the balance of organizations in this study the larger ones with budgets of $5 million or more. 13.5% have budgets greater than $40 million.

Not your typical sector profiles. The largest group of responding agencies (42.4%) identified themselves as being in the social/human services arm of our sector, with a distant second being education (19%). The diversity of the rest of the sector was reflected in the remaining numbers, but, obviously, in much smaller numbers. Interestingly, given the results that follow, 3/5 of the organizations (59.5%) identified themselves as being in the “maturity/sustainability” life cycle, with just over a third (34.4%) identifying as being in the growth cycle. The remaining groups said they were either in the start-up phase (first five years) or in decline.

“A breath-catching 81% of these organizations do not have a staff retention strategy. “

The focus of this research was a hot button: staff retention. Overall, a breath-catching 81% of these organizations do not have a staff retention strategy. Given the life cycle stages of the majority of these organizations (growth and maturity), the financial resources available (given the size of the majority of these organizations, they should have at least one dedicated human resource professional on staff; and, to be fair, only 65% of the over $40 million organizations did not have a retention strategy), and the fact that turnover rates have been a long-time concern of nonprofits, it is even more staggering to find organizations operating without an explicit retention strategy.

If nothing else, creating a retention strategy acknowledges that: a) a problem exists and b) it is a serious enough problem that you want to address it. The average turnover rate at these organizations was 21.3%, with the bulk of that (16.7%) being voluntary turnover. What makes it even more disturbing is that the majority of nonprofits are unprepared to address a major source of organizational disruption, as turnover isn’t just about having to hire anew. It is also about the day-to-day interruption of being down a person(s), and the human and financial costs that go along with a revolving door turnover. The number one category of employees with the highest levels of voluntary turnover is people under 30. We have known for a good decade, since the research first hit the boards (the Millennial Impact Report first started studying millennials in 2009), that millennials don’t stay long in jobs.

What else do we already know? The number one reason people gave (59.7% cited this) for their voluntary departure was the absence of opportunities for career growth—that upward mobility. The second most frequently cited reason (47.6%): compensation and benefits. The surprise here is that despite that the majority of participants in this study were large organizations—not the ones with flat organizational charts and five to seven employees—people were still leaving because of a dearth of growth opportunities.

How can it be that a 10, 20, or $60 million organization has no ladder bearing multiple rungs? Howe can an organization with a budget of double digit millions, be unable to figure out how to have a compensation and benefits package that is truly livable and competitive? Again, it is important to point out that we have known for decades that nonprofits compensation packages were out of synch with the real world and that something needed to be done.

What has happened? What have boards done? A whole lot of nothing, as talk without action amounts to nothing. And, we have known for a while that we needed to provide opportunities for growth and professional development. Again, what has happened?

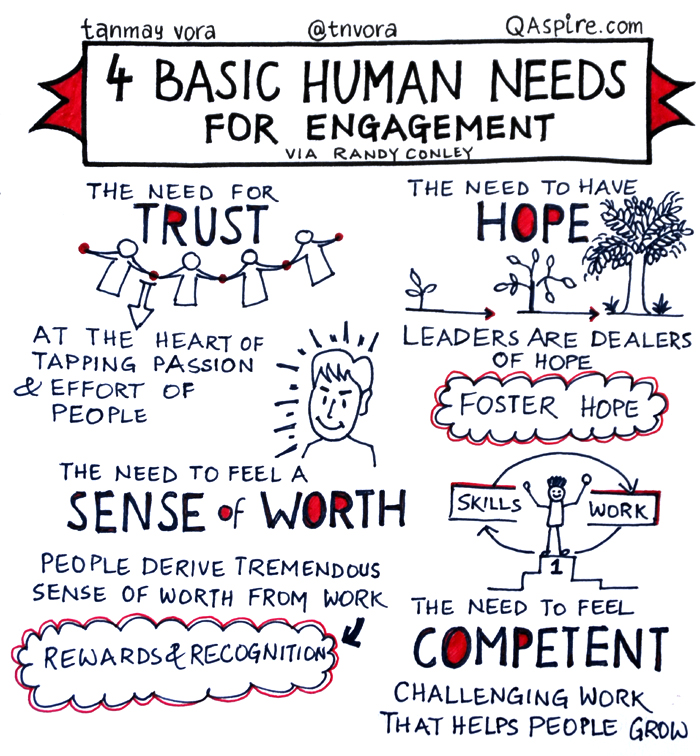

But there was something new in this data that should not get lost, as there is a much quicker (though not necessarily easy) fix to this problem than to the others. Almost half (47.7%) of those who left voluntarily pointed the finger at leadership as their reason for leaving: 26.2% cited “dissatisfaction/ disengagement with current organization/culture” and/or “dissatisfaction/disengagement with current leadership” (21.5%). Dissatisfaction with an organization’s culture, which leads to disengagement from the organization, lies at the feet of leadership (both paid and volunteer leadership, though most would think first of the paid leadership). It is a failure of leadership that creates a culture that disengages, and the success of leadership that creates a culture that engages people, explicitly values them and rewards them.

I wish the researchers had spent some time looking at the 5.2% who left an organization not by choice. We underestimate—and we don’t track—the damage done by this 5.2% that nonprofits notoriously allow to malinger far longer than they should. What is the average amount of time it takes a leader to finally step up to the plate and start the firing process?: the performance improvement plans, the three warnings, etc., the necessary documentation. How long do the employees who are stepping up have to suffer the toxic culture of (s)lacking employee still pulling in a paycheck?

And the final red flag: Nearly ¼ think turnover will increase in 2019.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.